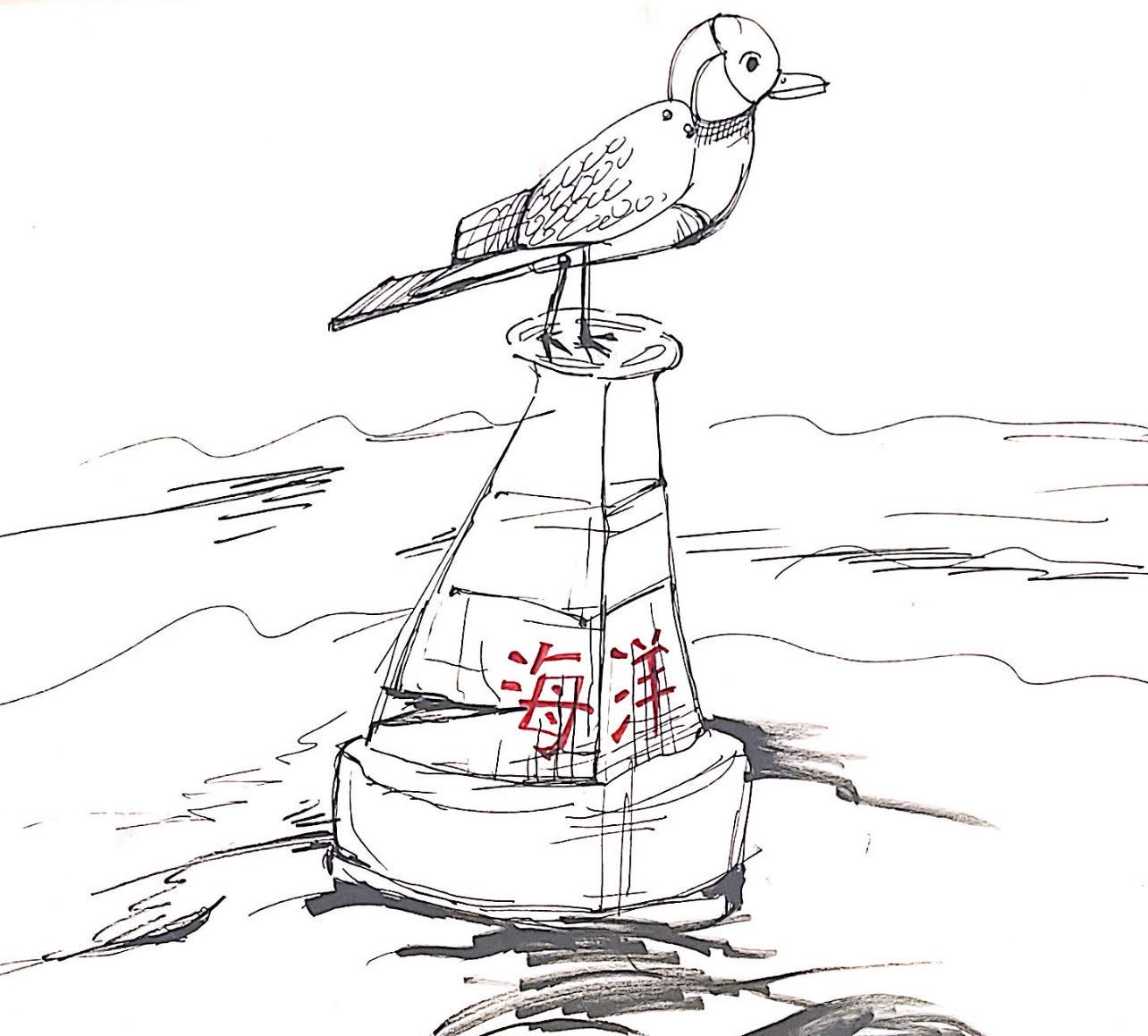

It bobbed there in the ocean chop, belly split, flakes of red lead paint stirring with the tide.

I rubbed the sting from my eyes and watched it float. Plaster-cast and valueless, jutting from the expanse. Taken for its worth and left to slowly sink.

Someone said something behind me but I didn’t hear it over the artificial gull-cries and the moaning sway of thousand-ton shipping containers. I couldn’t have cared less. I thought about ocean spray; what the real stuff must have sounded like.

Inside the buoy: fat digital stacks. Stolen from worse thieves, namely the Chinese up the beach. Intercept it, hack it open, strip its goods. All easy. All a matter of knowing you can. One of the other guys clasped my shoulder and showed me his phone. Little numbers flashed. An eight and a nine and a handful of happy zeros. The buoy vanished.

We followed each other off the dock and beneath the jungle vine electric wires of the upper alleys where we went our separate ways.

For a while I’ve been living like a bug in resin. Paying the drone for toiletries, getting dinner at the door, breaking unlucky hands with hammers — all the while drifting, drifting slowly in my gelatin mold. The coagulated man. This is lonely work, I’m saying. We don’t like each other. We don’t talk. We act afraid, like one of us might ask the other something scary.

And my head lately, God. Scratch my nose in the mirror and the reflection is liable to show the wrong hand reach up. Squeeze a greasy pimple and I start to hear giggles, no idea where from. I was doing this trick, waving my hand above a puddle of purplish ooze pooled in the sunken bend of the long cement dogleg that leads to my apartment. I was doing this trick and pulling my hand away — watching my reflection lazily follow, seconds, maybe minutes later — I was doing this trick and I got to thinking about my money. About spending some at Light’s Bar.

Light’s itself was all hard imitation cherry cedar and glass ornamentation. A warm-wood merchant hull in a sea of tidy concrete and mesh-cable clouds. A cash place, one of the last. The ATM outside was a polyglot, I’d never learned to read the signage, the jagged language. There, I did the litany:

Nobody exists — innocent man, innocent woman — nobody exists.

Type in my pin, take a deep breath.

Crisp purple bills spill out. The machine says thanks, I say thanks.

Men and women outside the imposing wooden door smoked illegal cigarettes. They looked at me like I was a cloud of methane. Nobody exists. Not the cops with body-cams murky with patina, not the Chinese fresh from their longboats, palms to heaven and scowling, carrying knives, stabbing them at the air. Nobody exists. But my hands shake, still.

Light’s. I want to say it’s where I go to rub shoulders and lament. I want to tell you my moments there; dreary and ecstatic, are something like a gift, that Light’s is some kind of way to pray. Where my fellow man and I convalesce but no. We lost that a long time ago. It’s a room where not a one of us knows the rituals. But our father’s father’s — maybe. The air between us is thick with rusted tension. Like the tense rope of an abandoned rig somewhere in the snow.

I pushed the heavy door along its slide. My corner seat was there (best feeling in the world) and I grasped the wood of the bar until it hurt the pads of my fingers, until the sweat on my neck began to cool.

Cats fed me my first highball. Hailing me with a nod, greeting me in my language. Illuminated there in trace neon, my Cats. All silhouette, equal parts shadow and technicolor. Arms crossed, hair like black thorns in a cascade. He tucked a mess of bangs into his headband and leaned in with elbows down and chin cupped and asked me, “Do you ike’ music?”

“I’m sorry?”

“Isten to piano?”

“I like it, yeah.”

“Shoji will open,” Cats nodded to a large partition, a wall that is sometimes not a wall, “Ady pays piano tonight. Very beauty-full.”

Through the unobtrusive dark I traced his nod. Along those couples-tables (single seat booths, face to face with a curtain to draw) where love and deals and breakups were meant to happen, I followed it past tall tables with solo skulking ex-patriots, past the big circle leather booth where expensive people (people I probably knew) looked bitterly at one another before laughing in stifled, manic fear before they returned to their drinks and dinner dishes and hopeful exasperation that this, that this night was not that night, where the person with a gun came in and erased them all. And then I spotted Satan and Gaul and Osiris, already dizzy and forgetting my itches, the two of them… of course I mean the guy from this morning, a partner I guess you’d say, and Ghastly. A big boss.

A tiny region of my brain replayed dry wall cracked by impact. Fingers dug into my side feeling for a vibrating organ waiting to pop. I smelt fried dough. Cumin spices. Familiar and warm. Cats had laid a dish and chopsticks near my outstretched hand and along with it — a second highball.

I popped a squidball in my mouth and drowned it and made a toast to the little person in my head:

I. Am but the figure of a man,

a woman. What-have-you.

All is well and well disturbs me.

A thing in the shape you consider, at the end of the hall.

What scares you at work, need not scare you here.

Such a thing, there is, I know, called territory.

Show your teeth.

It’s fine, show your teeth.

I was feeling, well, well I was feeling bare and insulted and then a noise,

or no, is this the toast? Hold on…

There was a felt-slip noise when the massive shoji pulled aside to reveal a woman in blue.

Her hair was pinned up with a silver butterfly in a style you’d see in a museum. Her blue dress draped purposefully in tatters at her arms and hugged her hips. She was fleshy but thin and she walked over the parapet and set the piano with a loud knock before keying a short mauve melody.

The bar fell silent.

“Thank you,” she said.

“This song is All Alone Am I by Brenda Lee,” she smiled at herself, at others, “I really love it.”

I felt inexplicable haste. Bodies. Blue dress diamond eyes matronly beauty. My heart hurt, hurt not like a metaphor I don’t mean love, it just hurt. I felt nervous. Utterly destitute. I wondered, what could I do? As my knee knock-knocked the bar-top.

Then the first chord came in and it all went away.

The woman began to speak-sing in the demure tone of the ancient past:

“My heart must hear to ever sing again,

“The words you used to whisper low,

“No other love can ever bring again…”

She croaked on softly. Matronly beauty with a contagious scratch in her throat. Cats silently cast another drink my way with a nod of commissary and I felt like ramming my head into the hard corner of the bar. Like a bear off the scent of its cave. Like a viking with jock-rot on an empty stomach.

At the end of her tune she stood and thanked the room. She apologized for the tone of the song, promised, with a trained soft rasp, more fun. Then she sat back down, straightened her spine, cleared her throat, and craned her pale neck in my direction, “Cats, gin with rosewater.”

I stared into the bitter vapor of my drink. At the bottom I saw rose petals that spelled out a word. It made me shoot straight up. Cats saw and asked, “Okay?”

I looked around. Everyone looked intentional and articulate. Like they had articulate intentions.

“Fresh air for a sec, Cats.”

“Okay, brother.”

Stepping into the cool night I turned to slide the heavy door behind me and the events inside the bar, framed by the door and the wall, looked something like a glimmering mosaic. The singer’s face at the focal point, frozen mid-song in vague emotion. Cats on the right-hand side behind the bar featureless but for the forest of black hair. Dozens of bodies as the foreground, not a face amongst them; and of course off in the corner, disconcertingly lit, a single large booth where Ghastly and my partner sat.

I closed the door. Probably, I thought, if I pulled the door again it’d open to a different place altogether— a fast-food stop in Kentucky, a cock-fight in Puerto Gal, a little stairwell in the bridge of one of the off-planet rides everyone and their mother’s are taking. But I went to the alley to piss.

Someone nearly doused my feet with pot water. The alley was dark but the flat kitchen door was propped open with a brick. A green beam of light crept to the tops of my shoes and I zipped up and stared into it.

I remembered something about the guy I’d worked with that morning, who was with Ghastly. He was from a part of China I’d been to, I’d met him there, actually. A place named for a mountain that reaches high enough to talk with God and look down at the sun. I’d went up there and it was freezing and dark. At the camp before the final peak people were handing out tough surplus coats from some war, the plateau was encircled by tall light posts emitting a similar color green as the color from Light’s kitchen door. Unpleasant and somehow reminiscent of labor, a washed ocean green. Like we’d gone so high we’d found our way back to the bottom.

I don’t remember how we got to talking. We ate bao and he told me a story about how his grandmother lost her arm as a child, how she made dumplings with one hand and how her hand was so strong from the years of fiver-finger-dumpling-craft that when she’d grab him by the wrist or pluck his neck or poke his chest he’d writhe in pain, and how to this day he can’t quite stand being touched by anyone for any reason. I had totally forgot. The sheer serendipity in meeting him again, years later and so far away, I had totally forgot. Things just go away. Gone inside and disappeared. Nobody exists. The mountain was high, my legs were so goddamn sore from the climb down and that’s it: experience and feeling replaced with information. The molecule changes and nothing is transposed. Not really. I should barrel out their skulls. A little magnetic ping and all the useless pictures stored in their heads gone. Ghastly? Big boss? Morning partner? Jazz enchantress? Nobody exists.

It felt odd going thing through the kitchen. I pulled the little brick in with me, nobody was there. Through the other side I came out nearer the blue songstress and crossed over, locking eyes with her briefly, telling her telepathically that this was all her fault. Ghastly’s big booth was empty but I had a hunch. He and my morning partner held up in a couples-booth talking business.

I drew the privacy-curtain hard but it just slunk disappointingly. They looked at me with interest that lasted about as long as a lit match on a log flume. When I looked at them I felt extremely guilty and full of love.

My morning-partner said my name. Ghastly extended a hand which I just looked at. They couldn’t ask me to sit. It’s not like I’d fit on either of their laps. I said, expertly, Do you come here often? And they both shook their heads and I said, expertly again, Impressive, please don’t come back again.

The piano cover closed with a clunk and Light’s became church-like again. The singer whispered she was taking a quick break. I pointed my finger in Ghastly’s face and kept it there. He looked like a wet cat in the dark, uncomfortably keen. His eyes were unfairly pretty but his teeth were a ruin. Then my arm got tired (I was still holding my finger up) so I turned away, slid the curtain back over them, and waltzed off to find the woman.

She sat alone at a table beside the piano like a mollusk out of its shell. Not smoking a cigarette or reading a paperback or anything cute like that, but looking at her phone, the glint in her eye told me it was a fancy phone, the kind that took in the peripherals of your vision. Disrupting her would be a slight hurtle.

I don’t remember what I said. I pretended to be clumsy and spilled her drink so I could get her another and show her I knew Cats pretty well; I coughed loudly and asked politely if she didn’t mind that I joined her; I found her online and liked two-hundred of her photos. Whatever sounds right. One way or another we got to talking and I got the sense she was made of blueberries and hand-whipped sweet-cream and entirely poisonous. She told me singing still made her nerverse. But then Ghastly came, and my morning partner clasped my shoulder and she had to return to her set anyway.

At the big booth we sat, and Ghastly, face lit in the bar-dim by a Gothic tungsten cistern, asked me what exactly it was, exactly, that I wanted? And I laughed, I said, “Just leave.”

We were at Light’s Bar, if you remember, and not at the bottom of the ocean.

Ghastly made a funny face that made me smile. Really, their faces were getting murky. Nobody exists. Ghastly’s features were like water poured over velvet. He said, “You know he’s like my son, so I was going to send him alone up there, as one of the chinks upstream is turning it over to me anyways. But it may be dangerous as dangerous things may be — OK? I like the feeling that my son is safe, so maybe you could use the money — and I promise we won’t come —”

I stopped hearing him. My morning-partner, who was lanky and bald with thin expressive eyebrows and a strong jaw, whose name was Carter, made some kind of gesture to me with his eyes and I was about to ask him how his grandma was if I could only shake the feeling I was about to cry. Then Ghastly asked, “So how about it?” And whatever it was I agreed. And before I could wave to Cats I was out at the docks with nothing but the beating of wings, which is what I say the ocean sounds like.

Black and green. Everything was painted with the same fat brush. Our little boat tarried. Stroke after stroke the waves came. Shoulders hunched, arms tucked between his legs, Carter, he was two strokes only: one broad downward, one heavy dot.

I was feeling crispy and roly-poly. I was going to embrace Carter and tell him we should be pals. I felt I was turning a corner, I felt so bad about before. I felt like a sugar cube being kneaded into dough. Carter was probably wondering where the buoy was, tracing the light pollution between shadow and reflection.

It occurred to me they turned the gull-cries off after dark. Then I saw it.

Lolling dumbly at the whim of the ocean surface, this one we’d call inverted. Its body was white and the identifying character painted across its plaster was red. Opposite of the morning’s haul. The color switch indicated some kind of propriety but that system changes. Basically, the illegal trade of information and digital currency was locked into this rigorous process and this outlandish means of retrieval. But we thieves have to adapt adapt adapt. I readied my net and unsheathed my knife and asked him, “Whats the inversion mean now?”

He stood and braced to grab hold of the buoy and steady the skiff, ignoring me. Which was fine, he could have all the time in the world to adjust to our new friendship.

My job was up. It’s a little delicate but most buoys are the same, two-three tries and you get the hang of it. The knife is for the plaster, you cut in with some force but avoid the wiring, the wiring is meant to connect to some electrical processor we made up that I won’t name. Data loss happens if you cut the wires, there can be sparks, bits fall out like gemstones from an elaborate necklace.

Carter wrestled the neck of the buoy into the crook of his arm then held his hand out gesturing for me to stay put. He sat very slowly, as if the boat would tip, and looked just above my head. Maybe the city had risen up behind me on two legs.

I said, “What?”

“Sorry,” he kept looking above me, “let me do this.”

“Why?”

“Can I just do this? Would you let me do it?”

“Okay—“

“It’s fine.”

“Okay.”

He reached for my knife and I handed it over.

Now it was me looking over his head. This was my part of the job and it wasn’t the harder part. My eyes began to cross at the dark nothing beyond him. The dark washed green crushed under the momentous silver and pink city reflection. The way it all congealed. I felt was no longer on the water but deep beneath, miles below. All my thoughts turning to gurgles. He said, “Sorry,” and he inhaled deep.

He held my knife to the buoy’s spine, keeping it steady in his lap like he was propping a dead kid upright. He looked straight into my eyes like he was searching for something.

“What are you doing?”

“I took money. But it was your mouth what got you.”

Asking permission into the night, he said, “Okay… just a second. Okay? Okay.”

“What? What are you saying?”

He shook his head slowly as he whispered, “There’s some honor in it some.”

He gashed the buoys neck, there was a brief static hiss before the burst of a million little pieces of sharp thin alloy bits and plaster pulp. It was as if a boulder of packed snow had exploded. He was gone: a ribboned mist of sinew and spray.

I felt hot all over. I felt the need to cough, deep in my chest. Then I was leaning back in the boat just trying to stay awake.

What a bummer, I felt for my old friend. If I could just think. All the lights were out, things were whirring down. The little push little pull of the ocean rocked me gently. Everything else was abstraction. I heard the singer’s voice in my ear telling me she was nerverse (hey, I feel nerverse too) and I felt thousands of hot holes in my body like acupuncture. Violent grandma, Cats’ glorious hair. A deep ugly green. The beating of wings. I felt lucky. It was my lucky day, I’d make it out! The beating of wings.

I knew I’d live, cause I was playing my little trick. This me was the reflection me, and I up there had already moved away. All this I felt while floating, the little push little pull of the ocean rocking me gently, as I was taken for my worth and left to slowly sink.